Chris Ware’s Building Stories: An Exploration of Space’, Kat Sicard, PhD Candidate in Design, University of Edinburgh

NOTE: This article was originally published on Infinite Earths on April 29, 2013. Here’s an internet archive that includes my post

A lot has already been written in a relatively short amount of time about Chris Ware’s remarkable new “book” Building Stories. (Book is in quotation marks as the story is told via a series of pamphlets, books, broadsheets, and an oversized screen that resembles nothing so much as a board game.) The Comics Journal ran a series of essays at the time of its release; contributors to Chris Ware: Drawing as a Way of Thinking were given the chance to revisit their essays which explored work previously published by Ware that eventually became Building Stories. (http://www.tcj.com/tag/building-stories-essays/) Philip Nel, who taught Building Stories last semester, helpfully has posted not only a plan on how to tackle the book with students, but a fairly comprehensive list of articles and reviews that have been published in the 6 months since its publication. ( http://www.philnel.com/2012/11/09/teachingware/)

As the general plot and character of the book are covered elsewhere, I would like to focus on the representation of place within the narrative, and the significance of locality to the interpretation of specific story-objects within Building Stories. I won’t touch on all of the objects within the box, leaving out 'Branford the Bee', and only glancing upon the pieces set in Oak Park, IL. I want to focus much more on the pieces that revolve around the old tenement-style apartment in Chicago itself. [Note: none of the four characters who inhabit the apartment building are named. It becomes clear over the course of the larger narrative that the main character is the female tenant who lives on the top floor. For ease, I will refer to her as such, and the other characters in relation to her: the downstairs couple, and the old landlady. Ironically, her cat is named, but she has given it the uninspired moniker Miss Kitty, so effectively is as unnamed as the rest.]

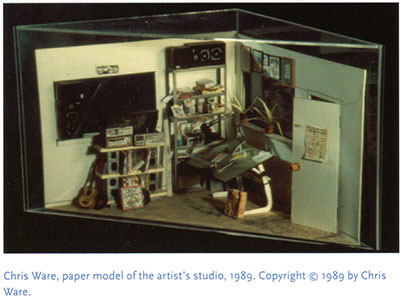

In order to get a better sense of the structure of the building he was constructing, Chris Ware actually built a paper model of it. This wasn’t the first model he has made, mind you, as there’s an image dating from 1989 in Tod Hignite’s In The Studio of a model he made for his grandmother of the apartment he was living in. She never had a doll house growing up, so when she asked to see what his studio looked like, he created this simulacra for her (Hignite p 250). Of course, the model of the apartment building is quite a bit larger, and more complex than previous attempts.

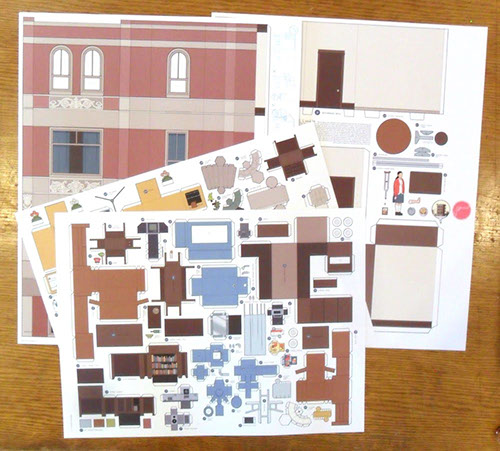

Ware also made a copy of the original building model to be displayed at a gallery show that coincided with the book’s launch. When creating the duplicate, he realized it would be no more work for him to make plans that others could use to recreate his building, and so a limited edition companion was created: a “13 sheet collection of dry technical drawings, paper thin walls and cramped psychological spaces.” (http://www.drawnandquarterly.com/shopCatalogLong.php?st=art&art=a3dff7dd568fe0).

Ware has said of these models “they’re something of a joke on memory, how we reconstruct things from our senses, literally rebuilding the world in our minds” (Irving).

The same might be said of the structure of the apartment building itself, a sort of off-kilter rebuilding, mash-up or pastiche of two apartments Ware actually lived in over the years, an amalgamation of a real and imagined Chicago. It’s “like a weird bad memory of or a misremembered version of two different apartment buildings… recombined” (Reid). Ware wanted to create a shell, much like the doll houses his grandmother never had, empty spaces filled with potential energy. We inherently want to make up stories to fill these charged spaces. Ware fulfills this need by not merely telling us about the current inhabitants, but, through the use of the building as a character, allows the reader to know the story of the building itself.

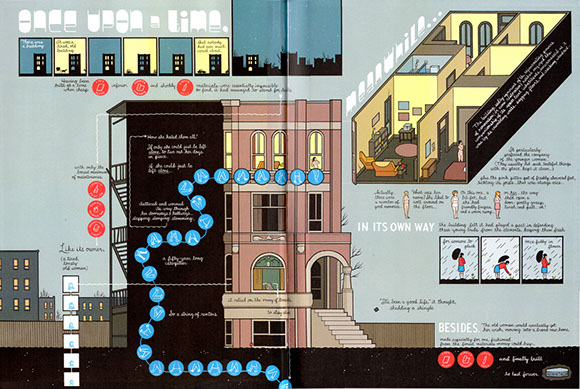

The embodied voice of the building speaks in the two hardbound books in the collection, providing an expanded framework for the story. While most of the stories in the collection focus on the building’s current inhabitants, the voice of the building reminds the reader that, while these may be unique individuals, little in the routines of their lives is significantly different from any of the previous litany of tenants over the past hundred or so years. This is not to say that each person is just a blank automaton fulfilling robotic gestures, dictated by the space they live in; the building has empathy for its tenants. When the woman downstairs storms away after a fight, the building plaintively calls her back, even though it knows that she will never be happy with her boyfriend. The building has a bit of foresight into the lives of its tenants, at least for the duration of their stay. Yet its own future isn’t so clear as it once was; the landlady is growing older and has no family to inherit the house once she passes away.

The realities of short leases, brief stays and a hurried city lifestyle may cause us to wonder if any trace of us remains in these places which anchor our daily lives. Do we leave psychological marks behind, as well as holes in the wall? When Jacob Brogan revisited pieces of Building Stories for his essay, ‘From Comics History to Personal Memory’, he discusses a sequence where the reader sees a tabulation of occurrences within the building’s walls:

Building Stories turns from problems of the collective past to questions of personal memory…. What we find here, then, is something like a sedimented record of all those everyday banalities that must go forgotten if we are to continue going about our lives. Like the apartment building itself, which disappears into the weave of the text as a whole, these are the things we leave behind as we mature.

The house is a repository for the collected lives of those who have come before, and the few yet to come.

While we leave marks on the places we inhabit, we must also acknowledge how much these places shape us as well. Tom McCarthy’s book, Remainder, is focused on a man who tries to exactly recreate a place he lived in an attempt to evoke a feeling he has lost. It’s something as subtle as passing between a couch and a counter while his shirt just barely tugs along a rough edge of the counter ledge that takes him back to the state of mind he longs for—a motion he performed countless times without ever paying it any mind, which etched itself into his subconscious. In an interview with Chris Mautner, Ware discusses this link between the physicality of space and mnemonics:

My incessant use of rulers is more of an attempt to get at how houses and buildings affect the shapes and structures of our memories, and how these shapes can continue to live on in our minds years or decades once the buildings are gone. For example, when one comes down a stairway day after day after day, something gets imprinted on the memory and the mind about rounding a corner and grabbing a banister in a very primal, almost non-verbal way. Even though it’s not an “image” exactly, that shape or the shape that movement creates is just as much a memory as how a house or a person looked at a given time, and it can shape dreams and even experiences, inducing recollections to arise at odd, unexpected times whenever a corner is rounded and a banister is grabbed.

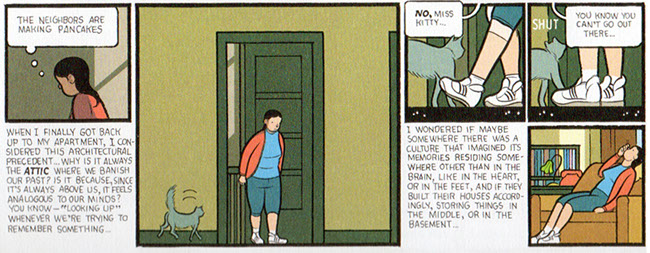

This physical deja vu speaks to how deeply we internalize the spaces we live in. In a way, this is the real-life version of the memory palace that Romans used as a mnemonic aid, associating certain facts or ideas with spaces in an imaginary room. Rather, actual memories are tied to the physical spaces and objects we mindlessly interact with daily. In his Globe and Mail article, Jeet Heer asserts that part of Ware’s genius is his ability to use architectural constructs to show the symbiotic relationship between building and residents. The main character even muses out loud about the link between architecture and memory after a conversation with her landlady. The older woman discussed her old artwork that is stored in the attic, leaving the main character to wonder:

Why is it always in the *attic* where we banish our past? Is it because, since it’s always above us, it feel analogous to our minds?… I wondered if maybe somewhere there was a culture that imagined its memories residing somewhere other than in the brain, like in the heart or in the feet, and if they built their houses accordingly, storing things in the middle, or in the basement (10am September 23rd 2000).

This concept is obviously more thoroughly realized in the sections pertaining to the apartment building, but there is still some semblance of these themes running through the Oak Park material. Truth be told, when I was first making my way through the box, I thought that the Oak Park material was divergent and was disheartened to see how much of the narrative was set there. But as I waded through the pieces and started to figure out that the whole story is filtered through the main character’s imagination, I started to appreciate the subtle cross-references that tie the whole work together. For example, in the aforementioned conversation, the landlady would never have said her art was in the attic, because she would have known that the building she spent her whole life in didn’t have one; that her things were all in the basement. The main character is only alerted to the lack of an attic when a previous tenant comes to fix her plumbing. While the home she moves to with her husband doesn’t speak in flowing cursive lettering, that doesn’t mean its character doesn’t have a similar impact on the protagonist’s life (Worden).

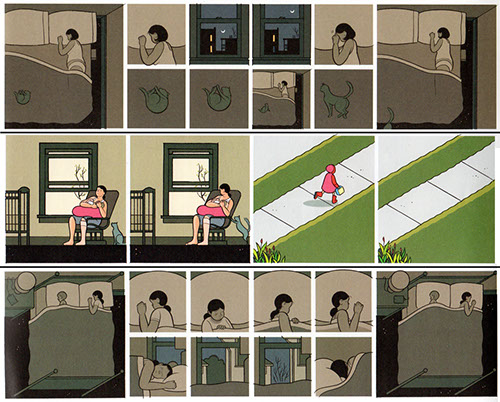

Ware plays with readers’ understanding of place in more ways than bestowing the building a voice. I found one of the slighter objects in the box to also be one of the most formally interesting. The primary conceit in Building Stories is that each person will make their way through the collected objects in a different order. The reader has to choose their own method, and I chose to read the story from the smallest objects to largest. This meant that I approached the silent, flip-book-style story fairly early on. I did not have the context from the larger narrative to frame this story-object, so took much of it at face value.

Upon first reading I worked out that each page seems to take approximately one season, and tracks the development of the protagonist’s daughter. I also made some erroneous assumptions. For example: the father leaves for work in the 5th spread and does no appear again until the 19th, originally leading me to think that perhaps the couple had split up or taken a break, when actually, I had missed that each spread also accounts for one hour in the day, chronologically, so he simply went to work and returned, albeit a fair bit older. I also took for granted that each of the rooms I was presented with were stable (i.e. the living room we are shown in spread 4 is the same as 7). As a reader, we assume a certain amount of stasis in the places we are shown. Yet the bedroom the protagonist is shown sleeping in shifts without any warning, and very little visual indication. On the first page, other buildings in urban Chicago are clearly seen, marking the setting as the apartment building, but in the 3rd spread, the protagonist looks out the window and sees the front path of her Oak Park home. Only after reading several other pieces did I become aware of enough of the larger story to understand this shift in place had occurred. Ware subtly betrays the reader’s expectations to foreground preconceptions surrounding place and location in traditional narrative.

Location grounds us in time, as well as space. My understanding of the change in location in the previous example came as much from my knowledge that the protagonist moves home around the time of her daughter’s birth as it did from the view out her window. Jeet Heer, Daniel Worden and Matt Godbey all draw attention to time in relation to Ware’s use of architecture, focusing on the apartment building as the locus for a shift in the perceived “historical scale” of the narrative (Worden). While Godbey argues that “Building Stories is… a project obsessed with [a] lived experience of time”, he also notes that the presence of the building, as a fixed point in a changing city, alters the reader’s perception of the time-scale involved in the narrative. The building acts as a sort of archive, locating the current cast of characters within a history of tenants whom they are, mostly, unaware of. The former inhabitant, now plumber, reminds the protagonist that she lives in the current version of the house, in the current version of Chicago. This notion is thrown into even sharper focus in one of the more jarring episodes within Building Stories; the reader is wrenched hundreds of years into the future, where a woman is accessing the emotional past associated with her location, and watches the actions of the couple from downstairs at an El stop. This is still Chicago, with its elevated trains speeding through the city, but it is not our Chicago of “now”, or the building’s Chicago of the early 20th century.

Ware utilizes locality and architecture to problematize the reader’s understanding of time and place in the multi-textual Building Stories. The looping cursive voice of the apartment building anchors the narrative’s past, at least as far back as the elderly landlady’s childhood memories. As Chicago grows around it, the building grounds its inhabitants. Each new tenant enacts similar patterns to the one who came before, be it kicking their shoes into the same corner or staring out the same window when planning their lives. We are seldom conscious of the patterns our dwellings instill in our lives, and it is perhaps the very effortlessness of these banal habits that imprint them so deeply in our memories. As Heer says, “All of us are boxed in. This sentence can be taken as a figurative description…, but it also happens to be literally true. We are born in boxes, live in boxes and die in boxes.” Ware deftly draws our attention to these innocuous moments and makes the reader aware of the importance buildings have in our lives.

Works Cited

Brogan, Jacob. 2012. 'From Comics History to Personal Memory'. The Comics Journal [Online]. Available: http://www.tcj.com/from-comics-history-to-personal-memory/ [Accessed 28/01/2013].

Godbey, Matt. 2012. 'At the Still Point of the Turning World: Chris Ware’s Building Stories and the Search for Structure in the Contemporary City'. The Comics Journal [Online]. Available: http://www.tcj.com/at-the-still-point-of-the-turning-world-chris-wares-building-stories-and-the-search-for-structure-in-the-contemporary-city/ [Accessed 28/01/2013].

Heer, Jeet. 2012. 'When is a book like a building? When Chris Ware is the author'. The Globe and Mail [Online], 05/10/2012. Available: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/books-and-media/book-reviews/when-is-a-book-like-a-building-when-chris-ware-is-the-author/article4591752/ [Accessed 28/01/2013].

Hignite, Tod. 2006. In the studio : visits with contemporary cartoonists, New Haven : Yale University Press, c2006.

Irving, Christopher. 2012. 'Graphic Novel and Comic Book Creators in New York City – Graphic NYC'. Graphic NYC [Online]. Available: http://www.nycgraphicnovelists.com/2012/03/chris-ware-on-building-better-comic.html [Accessed 28/01/2013].

Mautner, Chris. 2012. “I Hoped That the Book Would Just Be Fun”: A Brief Interview with Chris Ware | The Comics Journal. The Comics Journal [Online]. Available: http://www.tcj.com/i-hoped-that-the-book-would-just-be-fun-a-brief-interview-with-chris-ware/ [Accessed 29/01/2013].

Reid, Calvin. 2012. 'A Life in A Box: Invention, Clarity and Meaning in Chris Ware’s ‘Building Stories’'. Publisher’s Weekly [Online]. Available: http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/comics/article/54154-a-life-in-a-box-invention-clarity-and-meaning-in-chris-ware-s-building-stories.html.

Worden, Daniel. 2012. 'Loss as Life in Building Stories'. The Comics Journal [Online]. Available: http://www.tcj.com/loss-as-life-in-building-stories/ [Accessed 25/01/2013].

ABOUT

Kat Sicard recently completed a Masters’ at the Glasgow School of Art, where she explored definitions of “the book” and how interaction can shape understanding. During her time there, Kat became interested in the structuralist constructs that are inherent in how we understand comic books and created work around manipulating and subverting these constructs to challenge the reader. Currently, she is researching how comic books can be used to interrogate and analyze narrative structure. Kat is working on a practice-based PhD and will be making work that questions the form and format of the comic book and encourages the reader to engage with the work in non-traditional ways.